I’ve been reading about writing, editing, and creativity lately, and a theme that keeps popping up is the amount of time and hard work it takes to acquire natural born writing talent.

We’ve all read stories of “overnight success”–talented actors, writers, musicians, who seemingly burst onto the scene out of nowhere. What we don’t hear about are the years of hard work these overnight successes put into honing their craft, not to mention the innumerable instances of rejection. When it comes to overnight success, what it boils down to is this: when their moment to shine arrived, they were well-prepared. They were ready.

In her book The Creative Habit, dancer/choreographer Twyla Tharp discusses the phenomenon of the overnight success: “It is the perennial debate, born in the Romantic era, between the beliefs that all creative acts are born of (a) some transcendent, inexplicable Dionysian act of inspiration, a kiss from God on your brow that allows you to give the world The Magic Flute, or (b) hard work. … I come down on the side of hard work.”

Take Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, for example, widely accepted as a genius whose talent and skill came fully-formed and naturally to him at birth. That’s what this excerpt from Mozart’s Wikipedia page would have us believe anyway: “Mozart showed prodigious ability from his earliest childhood. Already competent on keyboard and violin, he composed from the age of five … .”

The thing is, we are all born with a talent, and often more than one talent. Part of the difference between someone born with musical talent who succeeds, and someone born with the same talent who does not succeed, is the luck of the draw. What the legends about Mozart often fail to mention is the family Mozart was born into. There was a clavier in the house, among other instruments. Mozart’s father, Leopold Mozart, was a talented musician in his own right–he was a violin virtuoso and even has his own Wikipedia page. He was a composer, played several instruments, and made his living as (get this) a music teacher. He noticed his son Wolfgang had musical talent when the child was a toddler, and he had the skills and the time to nurture that talent.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791 at age six

I mean, yes, Mozart wrote his first music compositions when he was four or five years old, but so what? I wrote and performed my first poems at the age of six and wrote a complete book series at the age of nine. The question for both of us is this: yes, but how good were they? Tharp notes that, “Even Mozart, with all his innate gifts, his passion for music, and his father’s devoted tutelage, needed to get twenty-four youthful symphonies under his belt before he composed something enduring with number twenty-five.” Okay, now I don’t feel so bad that my book series about two frog brothers never found a publisher.

The other difference besides luck, I firmly believe, is hard work. Talent and luck without hard work are candles in the wind, in my opinion–weak, fragile, likely to burn out. This was true even of Mozart, who had everything going for him. “Nobody worked harder than Mozart,” Tharp writes. “By the time he was twenty-eight years old, his hands were deformed because of all the hours he had spent practicing, performing, and gripping a quill pen to compose.”

Mozart acknowledged this himself. In a letter to a friend, he wrote: “People err who think my art comes easily to me. I assure you, dear friend, nobody has devoted so much time and thought to composition as I. There is not a famous master whose music I have not industriously studied through many times.”

I thought of these things recently, when I watched the movie King Richard, about the father of tennis greats Venus and Serena Williams. As the story tells it, Richard Williams and Oracene Price had two daughters with the intention of raising them from birth to be tennis greats. Both Williams and Price became tennis coaches in order to coach their daughters. They instilled a tremendous work ethic in their daughters, and the Williams family worked hard together and made many sacrifices, each and every day, to achieve their dreams.

Tennis stars Venus Williams and Serena Williams

I can extend this example to Will Smith, too, the actor who played Richard Williams in the film. I once heard actor Penn Badgley (You; Gossip Girl) respond to an aspiring actor who asked him how to break into acting. I wish I could find the exact quote or the clip–if I’m able to, I’ll add it here and share it on Twitter. It was so good. But basically, his response was to keep acting, to keep working at it. To practice. He pointed out that attorneys go to seven years of college before they can practice law, and doctors go to eight years of college and then several years of residency before they are fully licensed to practice medicine. Acting is a career choice, he said, and actors have to put in those same years of study and practice.

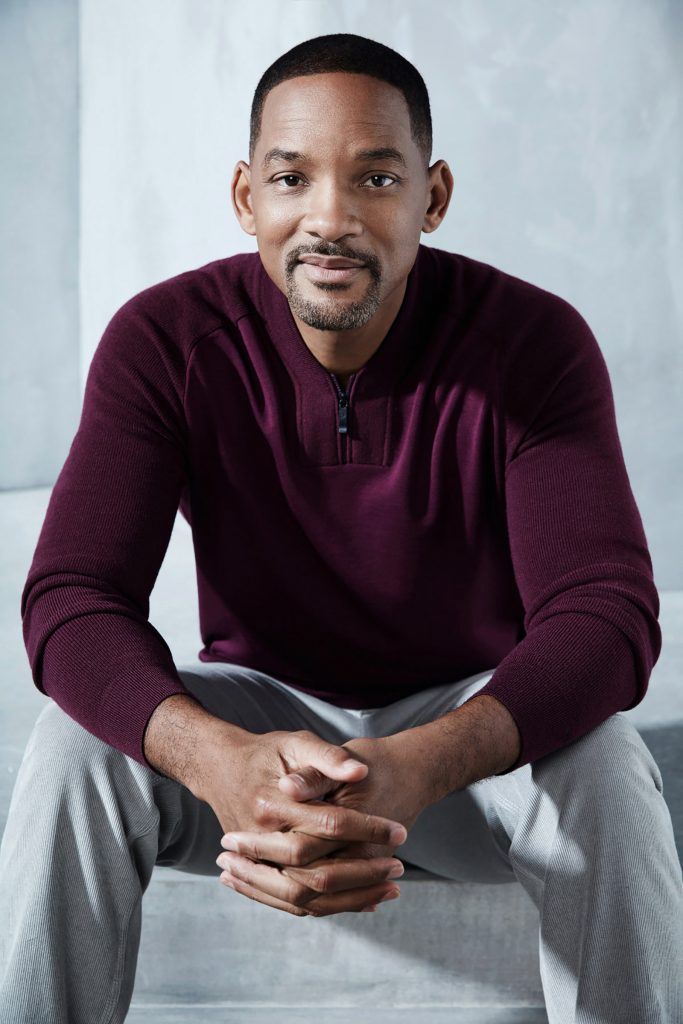

Anyway, my point is, Will Smith had been acting for 12 years before he received his first Academy Award nomination for Ali in 2002. That’s 12 years from The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air to greatness, and he was actually acting even before that, in music videos for “Parents Just Don’t Understand” and “Summertime” in 1989 and 1991. Smith was nominated for an Academy Award again in 2007 for The Pursuit of Happyness, and he was nominated this year for King Richard. Perhaps this is the year he will win. If so, it won’t have come out of nowhere. It will have come after nearly 25 years of hard work, commitment, and tenacity.

Actor Will Smith. Photography credit: Lorenzo Agius

If hard work = genius, then practice = excellence.

When I was a student in UC Riverside’s Palm Desert MFA program, I had the incredible good fortune to work on my short stories with Mary Yukari Waters for a year. Waters is an award-winning writer, the author of The Laws of Evening and The Favorites, and an exceptional human being. She’s won an O’Henry Award and a Pushcart Prize for her writing, and her own stories have been in Best American Short Stories … three times. When I struggled to get my words onto the page in the same brilliant way they came to me in my head, Waters explained not only the importance of practice, but its significance.

Consider this: Babies spend their first three years learning to talk. They begin making sounds at around six months. By the age of nine months they can understand a few words and begin to experiment with making many sounds. From around their first birthday to the age of 18 months, they learn to say a few words. By the age of two, they can string short phrases of two to three words together. By the age of three, they have a rapidly expanding vocabulary and begin to string short sentences together.

Although babies can only speak a few words at the age of 12-18 months, they can understand many more words–around 25 according to experts. Although they can’t speak sentences until around the age of three, they can understand them and respond to them. Last night, my granddaughter Louise, who is ten months old today, was trilling her tongue and saying, “ma-ma-ma-ma-ma” and “ba-ba-ba-ba-ba” and “da-da-da-da-da” on repeat. She was practicing. She can’t say the words, but she uses sign language to signal when she wants to “eat,” when she wants “more,” and when she’s “all done.” No, she can’t say the words, but she understands the words and their meanings. It’s all in her head, although she can’t articulate it in speech yet.

It’s the same with writing, Waters explained. When it comes to writing, we are like babies, with ideas in our heads, but without the ability to articulate them. The words are in our heads much sooner than we’re able to express them fully on the page. We are baby writers, and with practice, the words we write will more and more closely resemble the ideas we picture in our minds. It takes practice to get them from our brains and into our writing.

Mary Yukari Waters, author of The Laws of Evening and The Favorites

For a writer, perhaps nowhere does the hard work of writing show up more than in a writer’s devotion to rewriting. Revision. Self-editing. Hard work. In her book The Artful Edit, Susan Bell recalls: “There is a saying: Genius is perseverance.” Discussing F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterpiece The Great Gatsby, she writes with admiration about the intense work Fitzgerald put into the novel. She calls the novel “a tour de force of revision,” and she means that as a compliment of the highest order. Commenting on the words critics use to describe the novel, she concludes: “Careful, sound, carefully written; hard effort; wrote and rewrote, artfully contrived not improvised; structure, discipline: all these terms refer, however obliquely, not to the initial act of inspiration, but to willful editing.”

The bottom line is, excellence in writing (or in anything) is more a matter of hard work than innate talent. If you’re struggling with imposter syndrome after reading your contemporary literary heroes’ latest work, like I am, think about what it took for them to get there. You have those same tools at your disposal–hard work, dedication, persistence, perhaps a stubborn streak and a thick skin. Excellence and genius and mastery reside in you, too. Add hard work and practice, shake well, and pour it onto the page.