Last week, I discussed character descriptions that are almost entirely physical–they are focused on the character’s appearance. While they are good descriptions, they can be a missed opportunity. I’m a big fan of using character descriptions strategically, not only to describe the way a character looks, but to give us some insight into the character. So, I thought I’d go a bit broader this week and share a half dozen examples of character descriptions that go beyond the superficial appearance of a character.

Notice the different techniques the authors use to effectively reveal their characters’ personalities, struggles, flaws, and pasts. Also notice how much these descriptions accomplish, often in very few words. These descriptions take the writers’ characters from good to great.

JAZZ BY TONI MORRISON: VIOLET

“I know that woman. She used to live with a flock of birds on Lenox Avenue. Know her husband, too. He fell for an eighteen-year-old girl with one of those deepdown, spooky loves that made him so sad and happy he shot her just to keep the feeling going. When the woman, her name is Violet, went to the funeral to see the girl and to cut her dead face they threw her to the floor and out of the church. She ran, then, through all that snow, and when she got back to her apartment she took the birds from their cages and set them out the windows to freeze or fly, including the parrot that said, ‘I love you.'”

Photograph by Kevin Berne, Marin Theatre Company. From Marin Theatre Company’s 2019 production of Jazz. L-R: Dezi Solèy as Dorcas; C. Kelly Wright as Violet.

Photograph by Kevin Berne, Marin Theatre Company. From Marin Theatre Company’s 2019 production of Jazz. L-R: Dezi Solèy as Dorcas; C. Kelly Wright as Violet.

Thoughts: Here, Morrison introduces us to a character, Violet, and she does so without telling us what Violet looks like at all. She tells us a story about Violet’s past, and she does so in an interesting way. It’s not exposition; it’s a story from perhaps the most significant and traumatic day in Violet’s life. This makes it a small but fiercely engaging story in its own right, folded into and crucial to the bigger story. This powerful little story tells us more about Violet than a physical description ever could. Morrison deftly accomplishes characterization through the use of compelling backstory.

THE GREAT GATSBY BY F. SCOTT FITZGERALD:

JAY GATSBY AND DAISY BUCHANAN

If you’ve read The Artful Edit (and I suggest you do), you’ll know that F. Scott Fitzgerald spent a lot of time rewriting and revising The Great Gatsby until he got every detail just right. This kind of excellence isn’t a stroke of luck or innate talent–it’s achieved with a lot of hard work and perseverance.

Here is one of protagonist Nick’s descriptions of Gatsby’s smile from The Great Gatsby:

“He smiled understandingly–much more than understandingly. It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced–or seemed to face–the whole eternal world for an instant, and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favor. It understood you just as far as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself, and assured you that it had precisely the impression of you that, at your best, you hoped to convey.”

Now, consider this oh-so-brief description of Daisy from the same novel:

“Her face was sad and lovely with bright things in it, bright eyes and a bright passionate mouth.”

Thoughts: Neither of these character descriptions tell us what the characters look like. Not really. We aren’t told how Gatsby’s smile looks, whether he has a crooked mouth, laugh lines, thin lips, or shiny teeth. Instead, we learn how Gatsby’s smile makes people feel. As a reader, I feel the generosity of Gatsby’s smile–he’s one of those people who can make every person in a room feel like the only person in the room. He makes people feel seen. I get it. I can relate it to my own experiences.

And rather than learning what color Daisy’s eyes are or what color her lips are painted or what color her hair is, we learn that her face is “sad” and “lovely” and full of “bright things”–again, we come away with a feeling about Daisy and who she is.

Still, despite the lack of colorful adjectives, I find these descriptions quite visual–they invoke an image and a feeling. Here, Fitzgerald accomplishes characterization with the use of emotion.

JANE EYRE BY CHARLOTTE BRONTË: BLANCHE INGRAM

“Miss Ingram was a mark beneath jealousy: she was too inferior to excite feeling. Pardon the seeming paradox; I mean what I say. She was very showy, but she was not genuine; she had a fine person, many brilliant attainments, but her mind was poor, her heart barren by nature; nothing bloomed spontaneously on that soil; no unforced natural fruit delighted by its freshness. She was not good; she was not original; she used to repeat sounding phrases from books; she never offered, nor had, an opinion of her own. She advocated a high tone of sentiment, but she did not know the sensations of sympathy and pity; tenderness and truth were not in her.”

Thoughts: This first-person description may, on its surface, seem more tell than show, but every line is thought-provoking and delves deeply into who this character is in a way that is not only interesting, but surprising and even shocking. Brontë’s use of metaphor is brilliant. This is the first-person protagonist/ narrator’s perspective–Jane Eyre is recounting her observations about Miss Ingram. So, as with all first-person narration, this passage not only tells us something about Miss Ingram, but it tells us something about the protagonist, Jane Eyre, too, and the thought it takes to consider that is engaging for readers. Also, how reliable is this description considering the inevitable bias of a first-person narrator? These added elements make the passage deeply layered.

“GOOD COUNTRY PEOPLE” BY FLANNERY O’CONNOR:

MRS. FREEMAN

“Besides the neutral expression that she wore when she was alone, Mrs. Freeman had two others, forward and reverse, that she used for all her human dealings. Her forward expression was steady and driving like the advance of a heavy truck. Her eyes never swerved to left or right but turned as the story turned as if they followed a yellow line down the center of it.”

Thoughts: Wow, right? Who needs a physical description of Mrs. Freeman. This description of her facial expressions tells us all we need to know about this woman’s character and about who this determined or stubborn woman is. Again, this is a brilliant use of metaphor–we picture Mrs. Freeman as a strong and immovable semi-truck.

“THE ROYAL CALIFORNIAN” BY TOD GOLDBERG: SHANE

“‘I need a place near a karaoke bar, if possible.’ He had a hustle he liked to do where he’d bet people that he could make them cry and then he’d bust out ‘Brick’ by Ben Folds Five and every girl who ever had an abortion would be in a puddle. It didn’t make him proud, but he had bills to pay.”

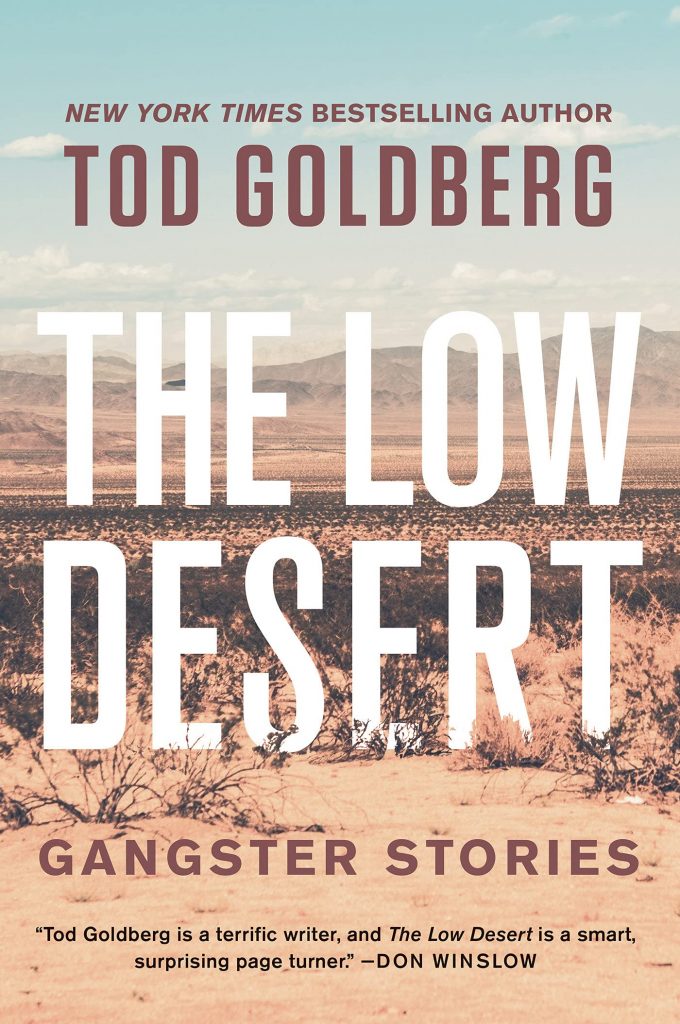

Thoughts: This passage is from the first short story in Goldberg’s 2021 collection, The Low Desert, which was just released in paperback. Here, the protagonist, Shane, is a karaoke DJ making a telephone reservation at a hotel, and he asks for “a place near a karaoke bar.” Then we hear why this is important to him, and we learn a great deal about Shane in just a few lines: he’s a hustler, he manipulates people with music, he’s not necessarily proud of it.

Thoughts: This passage is from the first short story in Goldberg’s 2021 collection, The Low Desert, which was just released in paperback. Here, the protagonist, Shane, is a karaoke DJ making a telephone reservation at a hotel, and he asks for “a place near a karaoke bar.” Then we hear why this is important to him, and we learn a great deal about Shane in just a few lines: he’s a hustler, he manipulates people with music, he’s not necessarily proud of it.

In addition to what we can learn about characterization from this story, it’s a masterclass in point of view too. “The Royal Californian” is written in such a close third-person point of view that it almost feels like first person. We are deeply inside Shane’s head as we read–this is exactly where you want your readers to be. Remember that, with first person, everything the narrator says or thinks or feels can help characterize them. Even if they are talking about someone else, we are getting some level of insight into who the narrator is. Here, Goldberg accomplishes the same thing with a skillful close third, which is remarkable.

TO THE LIGHTHOUSE BY VIRGINIA WOOLF:

CHARLES TANSLEY

“He was such a miserable specimen, the children said, all humps and hollows. He couldn’t play cricket; he poked; he shuffled. He was a sarcastic brute, Andrew said. They knew what he liked best–to be for ever walking up and down, up and down, with Mr. Ramsay, saying who had won this, who had won that, who was a ‘first rate man’ at Latin verses, who was ‘brilliant but I think fundamentally unsound,’ who was undoubtedly the ‘ablest fellow in Balliol’ ….”

Thoughts: What I love about this particular description of Mr. Ramsey’s friend Charles Tansley is that the third person narrator (here, Mrs. Ramsey) curates it–she gathers it like intel and compiles it like a dossier–all from information given to her by those around her rather than her own observations. Instead of telling readers about his appearance, Mrs. Ramsey relates a physically-adjacent description from the point of view of her children (“miserable,” “couldn’t play cricket,” “he poked” and “shuffled). The first two lines invoke an excellent visual image–we can see his bent, sickly body in our minds. Mrs. Ramsey’s oldest son, Andrew, contributes that Tansley is “a sarcastic brute.” Now we see him as broken-bodied, unhealthy, and ill-tempered. The characterization is then fully fleshed out through Tansley’s actions, specifically, the things he talks about on his walks with Mr. Ramsey. Although we haven’t really been told what Tansley looks like, readers now have a full picture of this character, inside and out.